Women in front of the first birth control clinic opened by the nurse Margaret Sanger in the Brownsville neighbourhood of New York's Brooklyn district in 1916. Social Press Association, New York, via: Library of Congress

Shortly before the US primaries in November 2022, Conservative Senator Lindsey Graham has sparked an uproar with a new bill. He wants to legally ban abortions across the country.

One US historian felt thrown back to late 19th century, when not only abortions were prohibited but the Comstock Act criminalised the circulation of contraceptives and any information about sex education. Especially women of the lower income brackets suffered on account of this. Their health was jeopardised by too many pregnancies and births, and they were left at a risk of poverty.

The mother of the nurse and women's rights advocate Margaret Sanger, for example, went through eighteen pregnancies in twenty-two years before dying of tuberculosis and cervical cancer at the age of fifty. Her mother's fate inspired Sanger's commitment to birth control. In 1916, she opened her first birth control clinic in the Brownsville neighbourhood of New York's Brooklyn district. Despite the police shutting it down after ten days and Sanger going to prison, a new movement had been born: the years that followed saw so-called Sanger Clinics opening across the US, and by 1940 there were already over six hundred of them.

In our study "The Impact of Margaret Sanger's Birth Control Clinics on Early 20th Century U.S. Fertility and Mortality", which has been published as a CESifo Working Paper and an IZA Discussion Paper, we digitalised data on the year of opening and the location of all clinics and combined it with historical full-count census data and birth and death register data in order to explore how these clinics affected the life and health of women and children. Here are our findings in a nutshell:

- After a clinic had opened, birth rates declined. Women with some kind of access to a clinic between age 15 and 40 had up to 15 percent fewer children.

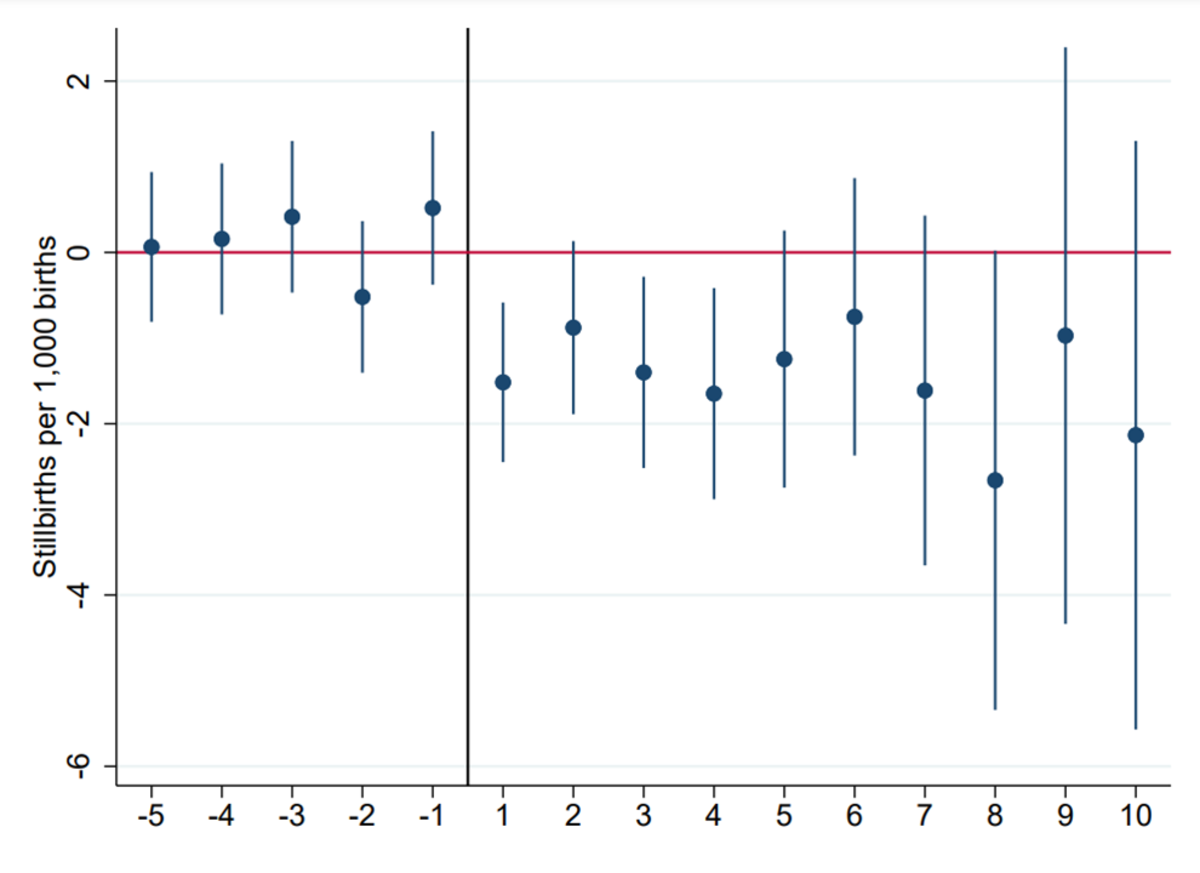

- After the opening a clinic, we find a 4.5 percent decrease in the stillbirth rate. This effect is not driven by a decline in the number of pregnancies but can rather be explained by a longer interpregnancy-interval, which improved the health of mothers and the (unborn) children.

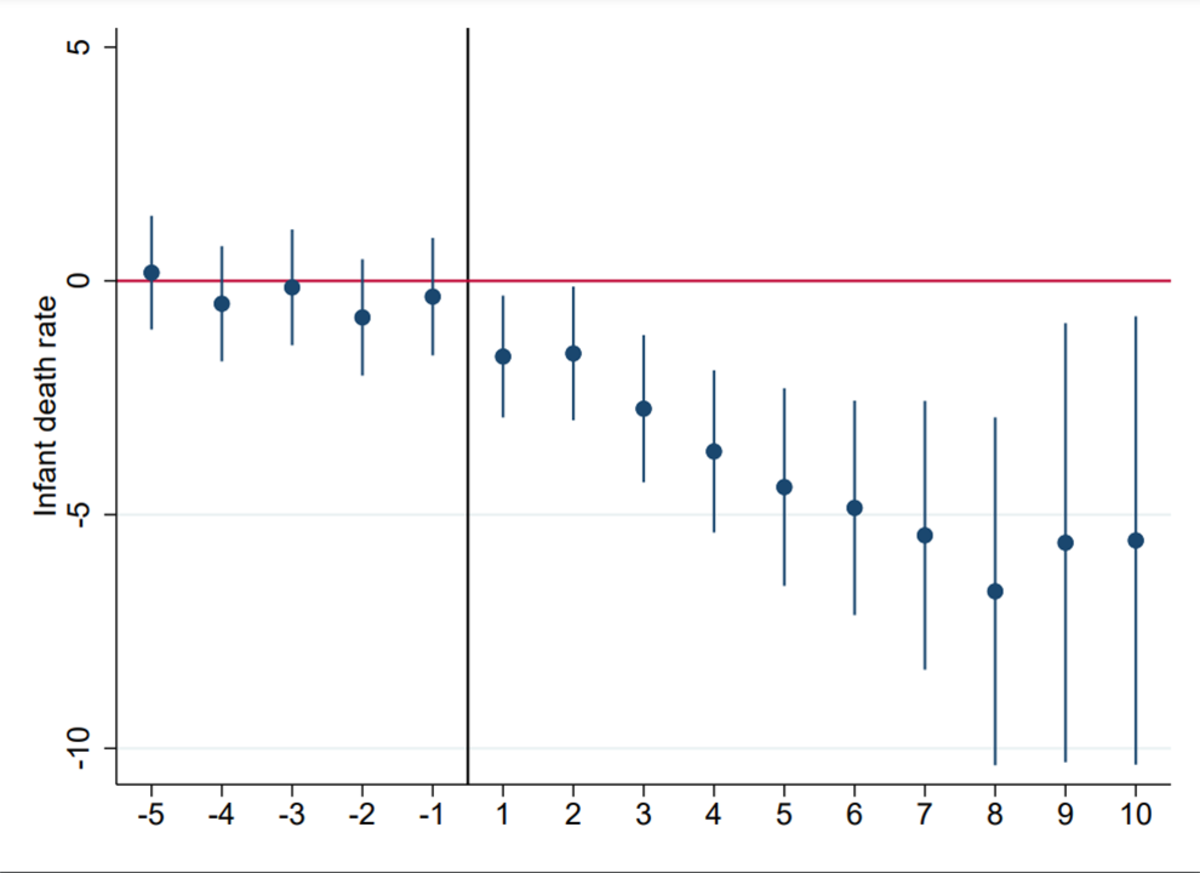

- Birth control clinics also resulted in a remarkable decline in infant mortality. We were able to show that, owing to the clinics, 7 percent fewer children died in their first year of life. Again, this effect can be explained by the improved health situation and is not mechanically driven by the decline in the number of births.

- We also find evidence for a decline in maternal mortality. In the period of observation, no sex-specific mortality statistics were published. However, cause-of-death statistics reveal that mortality from puerperal fever declined more strongly in regions with a birth control clinic than in other regions.

We have thus been able to demonstrate that the work done by the clinics improved the lives of women and children.

After World War II Margaret Sanger played key roles in the rise of an international planned parenthood movement and in the development of the birth control pill. Through these achievements she had a greater impact on the world than any other American woman.

Historian Professor James W. Reed, Rutgers, State University of New Jersey

Portrait of Margaret Sanger, via: Library of Congress

About Margaret Sanger and her clinics

The nurse Margaret Sanger was a vibrant personality who devoted her life to women's rights and birth control. Despite the praise she still receives today for her activism for women’s rights, birth control and planned parenthood, she has also been criticised for her closeness to eugenics and support for forced sterilisation.

When it came to "birth control" – a term she herself coined – her main concern was not to establish the right to abortion but to offer married women from low-income strata the possibility of extending the time between the births of their children through contraception and of reducing the total number of children to the number they wanted. At the time, many women had far more children than they actually would have wanted or were able to raise.

In her Brooklyn clinic, Sanger counselled women about contraception, fitted pessary rings and performed check-ups on women before and after childbirth. The demand was enormous: Over 480 women came in the first ten days before the police shut down the clinic. Sanger distributed fliers in different languages, founded the Birth Control League, engaged in legislative lobbying to promote legal reforms and risked imprisonment. After the first clinic opened, she had to serve 30 days in prison although she had demonstrably improved the lives of the women and children undergoing treatment, as borne out by our analysis of the historical data. Our co-author US historian Cathy M. Hajo, who has studied the life and work of Margaret Sanger in great depth, says that the women's right advocate would have been overjoyed by the results, as she had repeatedly asked herself what impact her commitment to the cause was actually having.

Our approach

For our study, we digitalised data about the roll-out of the clinics between 1916 and 1940. We used data that the historian Cathy M. Hajo had compiled from historical editions of the Birth Control Reviews published by Sanger, from newspaper archives and from many other sources. Overall, the digitalised dataset now comprises 639 clinics in 44 US states.

The map shows how the clinics spread across the country. The earlier a clinic opened in a given county, the darker the colour. First, they opened in major cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. Later, they also spread to semi-urban and rural regions.

We augmented this information using historical census data from 1920, 1930 and 1940 and focused on women between the age of 15 and 39. Overall, we were able to analyse information on 45 million women. In order to estimate women’s fertility, we relied on the number of their children under five in the household, an information recorded very accurately in the historical census data.

The results suggest that the clinics prevented births associated with an elevated risk for the women and children, for instance because they were occurring too soon after previous deliveries or the women had generally already had multiple births.

Professors Stefan Bauernschuster and Michael Grimm, University of Passau

We matched this data with annual data taken from the administrative birth and death records of historical counties. This allowed us to verify whether register data bore out the impact on the fertility inferred from the census data. We also used data to probe the clinics' impact on mortality rates. Methodologically, we made use of the fact that clinics opened in different years in different counties. That allowed us to factor out general time trends and differences in the birth and mortality rates between the counties and to ensure that the effects are actually attributable to the clinics themselves.

The results in detail

The census data revealed a sharp dip in fertility once a birth control clinic opened its doors. The decline ranged between 12 and 15 percent. We were able to observe this trend in the annual county-level birth rates as well (see chart on left).

The charts show the change in birth rate (left), the stillbirth rate (middle) and the infant mortality rate (right) in the years before and after a clinic opened (year 0). The dots on the vertical line show how the rates in counties with clinics vary from the rates in counties without clinics.

Apart from the decline in the birth rate fell, we also observe a decline in the stillbirth rate. The decline emerges in the first year after the opening of a clinic, it amounts to about 4.5 percent, and stays constant for the following 10 years (see chart in the middle). Infant mortality rates also diminished right after a clinic opened – by as much as around 7 percent (see chart on right). Both effects - the decline in stillbirths and infant mortality - are not just due to the reduced birth rate, but can be explained by a longer interpregnancy interval, which improved the health situation of the mother and the (unborn) children.

In some specification, we also observe a reduction in total mortality, although the pattern is less clear. As we were unable to obtain any sex-specific mortality data, we additionally collected administrative data on the causes of death recorded for major cities. In cities with a birth control clinic, mortality from puerperal fever decreased by 30 to 40 percent more than in other cities. At the same time, there was no differential change in mortality related to other causes of death, including cancer and heart disease. This allows us to conclude that birth control clinics reduced maternal mortality.

The results suggest that the clinics prevented the births associated with an elevated risk for the women and children, for instance because they were occurring too soon after previous deliveries or the women had generally had multiple births. As a consequence, the living and health conditions in the households improved as well, since fewer, but healthier, children sufficed to ensure financial security. In addition, the intervals between births increased and thus allowed women to participate more extensively in the labour market. This is also supported by the empirical analysis.

New insights regarding demographic change

From a historical viewpoint, our study contributes to the understanding of the demographic transition in the US which started to unfold in 19th century. So far, Margaret Sanger's birth control clinics have only been considered anecdotally. We are the first to show that these clinics had an impact that can actually be measured in quantitative terms.

Naturally, the results from the early 20th century cannot simply be transposed into the present day. However, they do allow us to infer how the demographic transition might be accelerated in several countries of the African continent, where birth rates are still very high: Sex education and family planning services can have a major impact when economic conditions change, the economic benefit of many children declines and the returns to children’s education rise. In such a situation many parents want to have a smaller family but do not have what it takes to do that.

The study “The Impact of Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Clinics on Early 20th Century U.S. Fertility and Mortality” by Professor Stefan Bauernschuster, Professor Michael Grimm (both from the University of Passau) and Dr Cathy M. Hajo (Ramapo College, New Jersey, USA) was published as a working paper in May 2023 in the series of the Center of Economic Studies (CESifo) as well as the IZA Institute of Labor Economics. A working paper is a preliminary publication in the form of a discussion paper that has yet to be peer-reviewed. Researchers use this format to have preliminary results critically assessed by other experts before they submit the article to a scientific journal with peer review.

About the team of authors

The economists Professor Stefan Bauernschuster and Professor Michael Grimm are currently researching into the impact of political measures at the University of Passau using similar methods but with different regional foci. Professor Grimm is concerned with countries of the global south, whereas Professor Bauernschuster has his focus on industrialised countries. Both have studied historical developments in fertility and mortality before: The present study builds on a paper in which Professor Grimm examined the impact of climate conditions prevailing at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century on the birth rate in agricultural households using historical US data. Professor Bauernschuster has previously explored how the roll-out of Bismarck's health insurance affected mortality rates in the German Empire.

While researching on the birth clinics, the two researchers reached out to US historian Dr Cathy Moran Hajo who had extensively researched the life and work of Margaret Sanger. In 2010, she had published the book "Birth Control on Main Street, Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916-1940", for which she had compiled the data on the clinics that Professors Bauernschuster and Grimm have now digitalised for the present study.

Professor Stefan Bauernschuster

How do political measures influence decisions made by individuals and families?

How do political measures influence decisions made by individuals and families?

Professor Stefan Bauernschuster has held the Chair of Public Economics of the University of Passau since 2013. Moreover, he is a research professor at the ifo Institute in Munich, CESifo Affiliate and a member of the Social Policy Committee of the German Economic Association. He is also one of the principal investigators of the DFG Research Training Group 2720.

Professor Michael Grimm

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

Professor Michael Grimm has held the Chair of Development Economics of the University of Passau since 2012. He is the Director of the Passau International Centre for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies (PICAIS) and one of the Principal Investigators of the DFG Research Training Group 2720 "Digital Platform Ecosystems (DPE)". Prior to this, he held the posts of Professor of Applied Development Economics at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Visiting Professor at Paris School of Economics and Advisor for the World Bank in Washington, D.C. (United States).

More information

- Margaret Sanger, Pionierin der Geburtenkontrolle - Report from German radio Deutschlandfunk quoting Professor Grimm (German, 15.12.2022)

- "Ich kann nicht dabei zusehen, wenn Leute leiden" - Report of SPIEGEL Geschichte (German, 10.11.2022)

- First birth control clinics reduced maternal and infant mortality in the US, study finds - Medicalexpress (14.11.2022)

- First birth control clinics reduced maternal and infant mortality in the US - press release on idw (Informationsdienst Wissenschaft, 14.11.2022)