Professor Michael Grimm holds the Chair of Development Economics at the University of Passau. He focuses his research on the resources of the poorest and conducts research projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, where demographic change is currently stagnating. His work gave him the idea to investigate possible causes in historical data. The study was published in the renowned American "Journal of Economic Geography".

The above video shows a farmer walking across the cracked mud surface of a dry dam. South Africa has been affected by extreme drought conditions, recently. Video: Adobe Stock

Professor Michael Grimm

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

Professor Michael Grimm has held the Chair of Development Economics of the University of Passau since 2012. He is also one of the Principal Investigators of the DFG Research Training Group 2720 "Digital Platform Ecosystems (DPE)". Prior to this, he held the posts of Professor of Applied Development Economics at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Visiting Professor at Paris School of Economics and Advisor for the World Bank in Washington, D.C. (United States).

It is well-known that children in poor, rural regions are used for old-age provision. However, this alone does not explain why the demographic transition is stagnating in some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. The people there are extremely risk-averse, they have a lot to lose. If they suffer economic damage, such as crop failure, they risk slipping into extreme poverty. Often, they are unable to get out of this situation.

But why do they decide to have more children anyway? My thesis: In poor, rural regions, children not only provide for old age, but also function as an insurance against feared damage, such as crop failures. Children engage in household chores and thus allow older family members to spend more time working in the fields or in the non-agricultural sector. With increasing age, children can also directly contribute to earning an income in hard times.

I can support this thesis with the help of historical data on the demographic transition in the USA, which really took off in the period from the Civil War to the Great Depression. The phenomenon and theory of the "demographic transition" refers to the historical shift in demographics from high birth rates and high infant death rates to demographics of low birth rates and low death rates. For hardly any other country is historical population data as well prepared and accessible as it is in the USA. The census data is now also available online via the "Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS USA)".

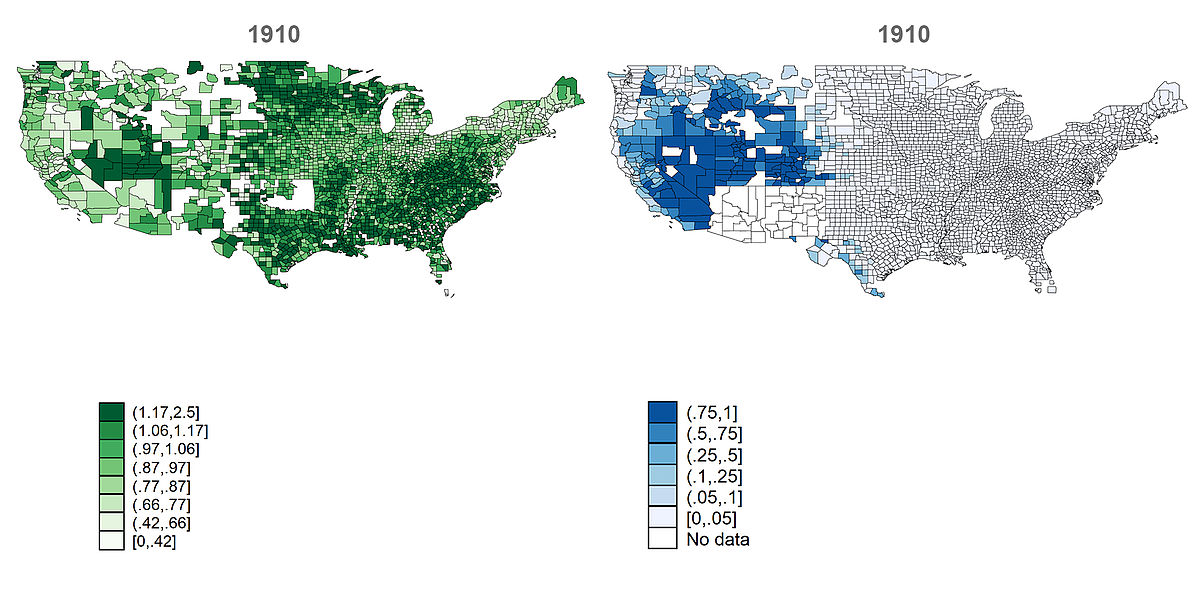

I concentrate on data like this in my study. Four different sources were included – population, weather, agriculture and banking. With the help of weather data, which was very small for areas of 16 square kilometres each, I determined the average amount of rainfall and rainfall variability for each individual county. From the census data, a total of 945,038 observations on women between 15 and 39 were included (for the exact method, see Paper, Section 4).

Fertility rates over counties and time

Parallels to the current situation in sub-Saharan Africa

The framework conditions in this period show many parallels to the current situation in Sub-Saharan Africa. A large proportion of US households were active in agriculture, especially those settlers who spread to the West. There were no machines, the capital stock was zero. In many areas, there were strong weather fluctuations with changing periods of too little or too much rain. The bitter drought of the 1930s went down in history as the Dust Bowl. People had to struggle with hard times, for example in the winter of 1886, when millions of cattle froze and starved to death, or in 1918, when the Spanish flu broke out.

My analysis shows that farming families in areas with severe weather fluctuations had more children than in regions with less severe weather fluctuations. The effect that strong rainfall risks or risks of drought are a driver of fertility is robust to a wide range of controls such as potential structural differences between areas with high and low weather fluctuations are taken into account (see Paper, Section 5.2). The reason is that children, and especially young adults, were able to work on farms and in other areas during difficult times. They were able to support the household financially. They were therefore a valuable insurance substitute, despite the initial costs of raising the children.

The need for this insurance diminished with the introduction of irrigation systems, modern agricultural methods and banking. In connection with the irrigation systems, I could see the greatest effect: The fertility differential due to rainfall variability disappears if the share of irrigated land in a county exceeds 23 per cent.; the birth rate then resembled the one in areas with small rainfall variability. Irrigation systems meant that the farms no longer had to fear being helplessly exposed to the risk of damage, for example from droughts. A significant effect could also be observed in the use of machinery. The emerging banking sector played a minor role, although it offered the possibility of saving and borrowing.

Fertility rates and share of irrigated land

Security aspect in times of climate change

Historical data provides important insights for current development policy challenges: Demographic transition is already stalling in some regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, blocking economic development there. Climate change – and thus the increased risk of extreme weather conditions – could exacerbate this situation even further. In order to accelerate demographic change, future measures must not only bring about structural change towards a modern economy, but must also take particular account of the aspect of security, for example in the form of health insurance or social security networks.