Holocaust memorial in Berlin. Credits: Adobe Stock

A "dark-field study" is to be implemented in North Rhine-Westphalia to shed light on the spread of antisemitic prejudice and resentment in society. This was announced by North Rhine-Westphalia's Minister of the Interior Herbert Reul und Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, the state's antisemitism commissioner. Professor Lars Rensmann, political science scholar at the University of Passau, will be heading the study jointly with the sociologist Professor Heiko Beyer from Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf. Professor Rensmann's research interests include the study of authoritarianism, antisemitism, populism and right-wing radicalism around the world using a comparative approach.

What do modernised forms of antisemitism look like?

Professor Lars Rensmann: Today, modernised antisemitism specifically manifests itself in three forms: Firstly, as the relativisation of the Holocaust, in other words, the need to mention and downplay the Holocaust and to disparage the memory of the Jewish victims by demeaning the memory of the Holocaust and thus to articulate resentment toward and discrimination against Jews. The second consists of new forms of conspiracy myths. It has always been only a small step from conspiracy thinking to antisemitism as a lens through which to view things: Anyone who thinks in ideological conspiracies ends up talking not only about Bill Gates but also about Jews. The third form is antisemitism relating to Israel, in other words the articulation of antisemitic resentment in reference to Israel and the hate for the existence of the Jewish state. All three forms are in fact not new. Antisemitism has been the conspiracy myth per se since Antiquity, and National Socialists already saw themselves as anti-Zionists. But these three modernisation pathways have facilitated many different ways and ever new forms of expression to articulate antisemitism without such postulations being understood as antisemitism and without members of the public perceiving themselves as antisemites. A new phenomenon is also that, in the quasi-public space of social media and on account of such media, the inhibition threshold for articulating such resentment has dropped significantly, in many cases bleeding over into outright hostility towards Jews.

The aim of our study is not to find out how widespread antisemitism is but to better understand and explain the factors that cause members of the public to be receptive to antisemitic ideas and conspiracy myths.

Professor Lars Rensmann

What is a dark-field study?

Rensmann: The term is adapted from criminology research: dark fields are the areas missing in official statistics. We actually still know too little about the dark field of antisemitism. We know too little about its occurrence, sundry iterations and their persistence in various milieus, in respect of demographic factors, but also too little about when the inclination to express antisemitic resentment or to fall in with antisemitic attitudes increases. Representative surveys conducted so far frequently resort to standardised questions that fail to sufficiently consider modern forms of antisemitism. With our research, we want to include situational factors and systematically take into account that respondents often answer in a way they believe is socially desirable and acceptable. The aim of our study is not to find out how widespread antisemitism is but to better understand and explain the factors that cause members of the public to be receptive to antisemitic ideas and conspiracy myths.

How do you go about your research?

Rensmann: We are using standard interviewing tools from representative research but have decided for the first time to combine these with the experimental survey designs that are available in social research but have never before been implemented in antisemitism research. In doing that, we hope to obtain more differentiated and valid results. We are working with research tools that we have tested in other contexts. Our method centres around interviews that are conducted in people's homes and take up to 45 minutes each. At present, we are busy developing the questions for these interviews. Our intention is not only to ask about attitudes but to employ new methods so as to gain a better understanding of the spread and the causes of antisemitic mind-sets in different social and political milieus. We also want to gauge the extent to which the particular situation and social context play a role. What happens, for instance, when an influencer expresses a particular view on the web? Or when a presumed majority holds an antisemitic position? Does that change the respondent's view? The interviews will be conducted on a representative basis. To ensure that, we have teamed up with a polling institute.

I believe that how we as a society react to antisemitism and other forms of hate speech is one of the decisive factors.

Professor Lars Rensmann

What do you expect from the study?

Rensmann: My previous qualitative research corroborates the following picture: That which can legitimately be said, plays a very big role. One of my hypotheses is that the potential of antisemitic resentment increases and decreases depending on the conditions of the situational context. This also means, however, that institutions need to create situational conditions where people who feel such resentment are not encouraged to express it. In my view, it is crucial that certain things – not only antisemitism but also racism, disabilism and other forms of unqualified exclusion and inhumanity – simply stay unacceptable, that they should not be part of a legitimate conversation, that it is not okay to express yourself in a manner that collectively disparages or demonises other people in a discriminating manner. Such remarks have nothing to do with the freedom of expression. Rather, they make free speech between people impossible. I believe that how we as a society react to antisemitism and other forms of hate speech is one of the decisive factors.

What role do parties of the extreme right play in pushing the boundaries of what can legitimately be said?

Rensmann: Right-wing parties and authoritarian populists are key players in the dynamics of public polarisation and radicalisation that drive such erosive processes. An example of pushing the envelope of what is considered "legitimate" public discourse comes from the US where I lived for many years: I felt I no longer understood this country when Donald Trump, an authoritarian populist, made fun of a physically handicapped journalist and then actually went on to win the presidential elections in 2016.

In earlier studies, I demonstrate how an erosion has taken place in Germany and Europe in terms of the limits of what is acceptable in discourse in the field of antisemitism and how the radical right-wing parties played a decisive role—but by no means only radical right-wing operators.

Professor Lars Rensmann

But we are witnessing an erosive process in many countries, also when it comes to antisemitism. In earlier studies, I demonstrate how an erosion has taken place in Germany and Europe in terms of the limits of what is acceptable in discourse in the field of antisemitism and how the radical right-wing parties played a decisive role—but by no means only radical right-wing operators. Last year, I pointed out in an analysis that the Alternative for Germany party (AfD), for example, exploits antisemitic resentment to mobilise its voters. Overall, however, it has become increasingly legitimate to make covert and sometimes even overt antisemitic remarks in public and to present oneself as the victim of unfounded accusations when such remarks were criticised.

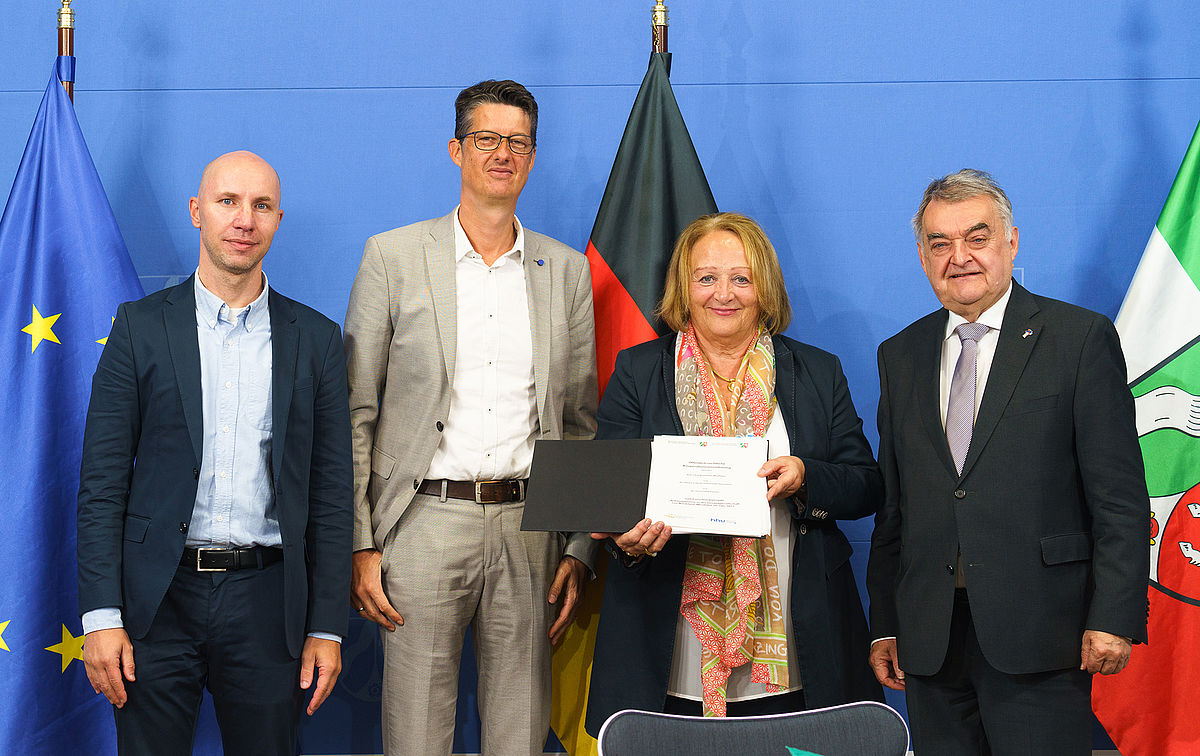

Professor Heiko Beyer (HHU, from left side), Professor Lars Rensmann (University of Passau), Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger and North Rhine-Westphalia's Minister of the Interior, Herbert Reul at the presentation of the study. Credits: Land NRW / Martin Götz

Why are you conducting the study in North Rhine Westphalia?

Rensmann: That is primarily because the state of North Rhine-Westphalia has a very active antisemitism commissioner in Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger. She pushed for this specific project and gave us an opportunity to share our research experience. We are also in touch with Ludwig Spaenle, Bavaria's antisemitism commissioner, because we want to make sure our scholarly expertise is brought to bear in the fight against antisemitism here at the University of Passau. I would like to mention that I consider the creation of such commissioners at federal and state levels as well as in the judiciary over recent years a very positive development. I am delighted to see that they make it a point to seek academic support in their work. Based on the findings of our study, we intend to develop guidance for action that can be taken by different institutions and educational organisations to effectively and sustainably fight antisemitism.

Interview: Kathrin Haimerl

Professor Lars Rensmann

What new and old risks does democracy face in the digital age?

What new and old risks does democracy face in the digital age?

Professor Lars Rensmann has held the Chair of Political Science with a focus on Comparative Government since the summer semester of 2022. Before that, he served as professor for European policy and society at the University of Groningen, as associate professor of political science at John Cabot University in Rome and as DAAD assistant professor of political science at the University of Michigan. In his research, Professor Rensmann studies crises of democracy, authoritarianism, antisemitism, populism and right-wing radicalism around the world using a comparative approach. He is currently conducting a "darkfield study" in North Rhine-Westphalia to shed light on the spread of antisemitic prejudice and resentment in society.