Monday morning, 7.10 a.m. It's belting down as I apply the brakes on my bicycle on the station forecourt. I push it towards the sheltered bicycle stand, but stop after only a few steps by a car which is waiting at the exit with its engine running. Water splashes from the hood of my anorak as I tap firmly on the driver's window. The senior citizen in the car interrupts his telephone call with a frown. "Excuse me," I say, "would you mind switching your engine off?" I'm on edge. "There's no way I can ride my bicycle long enough to compensate for your CO₂ emission as well."

It's experiences like this that make me angry time and time again. And when I get angry, I become unjust. I feel that the elderly gentleman is behaving in a way that is inconsiderate towards my generation. I see him as symbolising a generation which appears to be living on the principle After me, the deluge!"Wir sind hier, wir sind laut, weil ihr uns die Zukunft klaut!" ("We're here making ourselves heard because you're robbing us of our future!") is what we often chanted at Fridays-for-Future demonstrations in the times when such demonstrations were still allowed. Whilst we younger people eschew activities in these times of the pandemic out of solidarity with the older generation, solidarity with us on their part is a thing I certainly miss in the climate crisis. Instead, our society seems to be split by a generation conflict which is being fought out in the living-rooms of the republic. How on earth did things get this far?

Demographic change in Germany

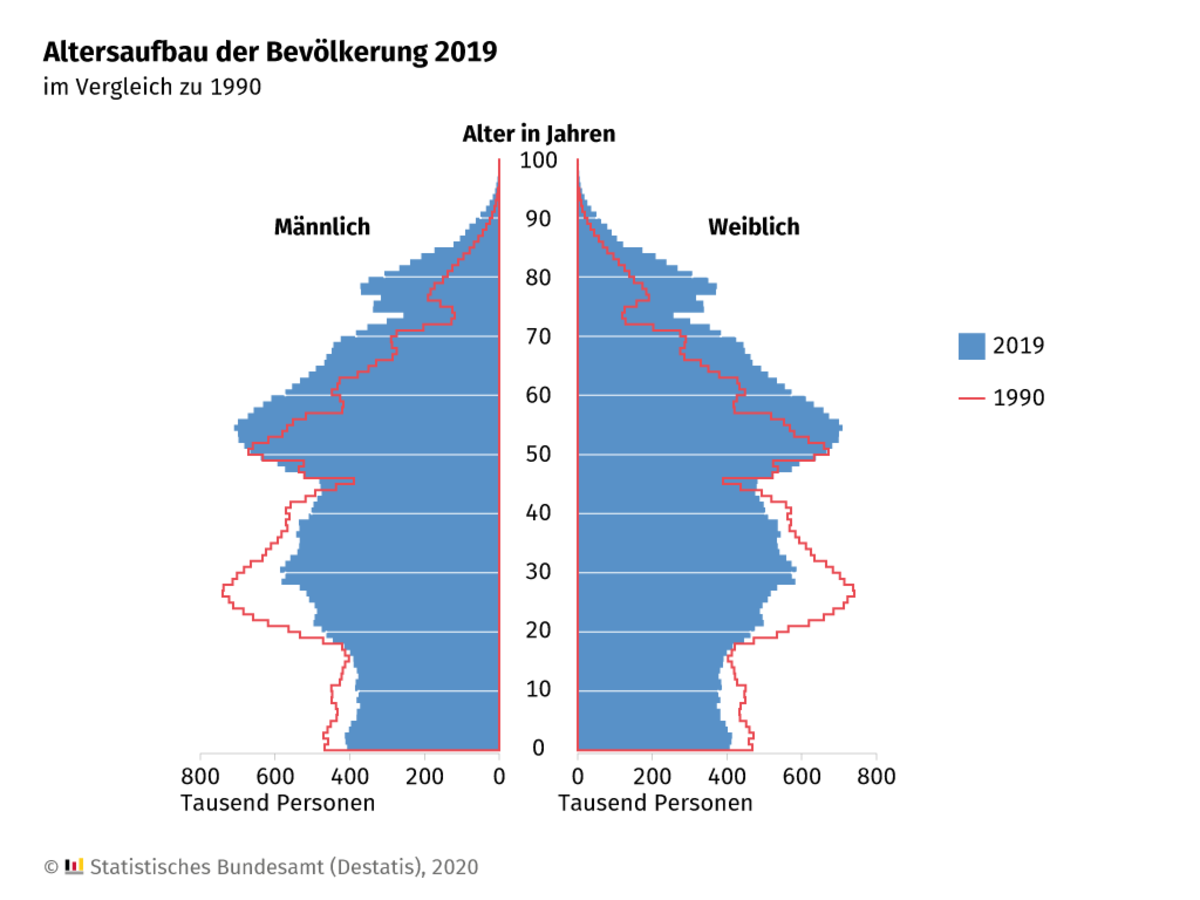

As a result of demographic change, every other person in Germany today is older than 45. Because the baby boomer generation, which had a high birth rate, are getting older and older, the population pyramid for the Federal Republic has changed since 1970 from being the shape of a Christmas tree to being the shape of a skewered kebab. That is also attributable to the low birth rate, which has been on the decline again since 2016 and is currently at 1.54 children per woman. So all in all, there is a generational imbalance in Germany.

Deeper entrenchments

Vociferously, the young generation asks awkward questions relating to responsibility and justice – the accusations they make are levelled mainly at the baby boomers, who are now aged between 54 and 63. Young people are not prepared to accept the fact that they, who have contributed least to the climate crisis, are going to have to grapple longest with its consequences.

At the core of this generation conflict there are notions which are closely connected: responsibility and blame. First there is the question of responsibility for the past, for climate sins and wasted opportunities. Secondly, this is about responsibility for the present, our current behaviour, and inactivity. That leads to the third stage: responsibility for the future, which is influenced by decisions made today.

Professor Peter Fonk is Professor of Theological Ethics at the University of Passau. He deals regularly with ethical-moral matters of conscience. As he sees it, the aspect of the past is certainly important, but it should not be where the debate ends: "I'm sceptical about whether concentrating on the question of blame will help. If we do that, we run the risk of getting into a rut of permanent self-accusation, which will not help anyone. Apart from that, this accusation creates a defensive attitude which is obstructing the constructive dialogue. Yes, blame needs to be talked about, but the discussion mustn't stop there. If it does, we're not going to get any further."

Professor Peter Fonk

What ethical principles do the managers of tomorrow need?

What ethical principles do the managers of tomorrow need?

Professor Peter Fonk has been holder of the Chair of Theological Ethics at the University of Passau since 1994/95. He is director of the masters study programme Science of Charity and Value-Oriented Management and of the Institute of Applied Ethics in Economy, Education and Training. The emphasis in his research is on Christian social ethics, economic and corporate ethics.

As far as the present is concerned, a new obstacle has been emerging, as Professor Fonk explains to me: 'In our modern society there is the problem that it is no longer possible to attach responsibility so firmly to individuals, because it is often anchored in structures and institutions.' That doesn't just make it more difficult to call a specific person to account. That distribution also gives rise to an anonymous, collective responsibility to which people feel less committed. In concrete terms that means that if lots of citizens regularly fly to holiday locations, each individual one of them feels less guilty for doing so, especially because that activity doesn't have any consequences of the kind that could be felt directly, but instead only consequences for later generations. Moreover, this collective responsibility often leads to the absurd argument that as an individual, no-one can make a difference anyway.

"Short-term thinking and egoism are the death of all ethics."

Professor Peter Fonk, Chair of Theological Ethics at the University of Passau

So distributing blame on many pairs of shoulders makes it easier for individuals to deny responsibility. But I'm not prepared to accept that. Evidence of climate change and the catastrophic impacts of the way we live has been on the table for decades. As far back as 1895, the Swedish physicist Svante Arrhenius recognised the consequences of the anthropogenic greenhouse effect. Does the fact that people are still not getting the message perhaps have something to do with the way information on the crisis is communicated?

'No', says Professor Hannah Schmid-Petri, who conducts research into public debates at the Chair of Science Communication at the University of Passau. In her opinion, communication is too often seen as a panacea. The problem is much rather that climate change is a very abstract thing, in other words it cannot be experienced directly in our everyday lives: "Ideally, a person who gives up smoking notices an improvement in his or her health after only a few days. It's not as simple as that with the climate. If we stop flying today, we won't notice after one week that the climate is improving." So it is all the more important to make a clear link to people's actual everyday life when communicating solutions. As a whole, reporting about the climate crisis is often very negative. Instead of focusing on nightmare scenarios, the public debate ought to focus on approaches to solving the problems. That is a trend of which Professor Schmid-Petri says she can already see some initial signs. 'Finally, however, it's the way we are preconditioned, our social surroundings, our family and their standards and values that most influence the way we behave', she says.

Professor Hannah Schmid-Petri

How are digitalisation issues publicly discussed and what consequences does that have for political processes?

How are digitalisation issues publicly discussed and what consequences does that have for political processes?

Professor Hannah Schmid-Petri is the holder of the Chair of Science Communication at the University of Passau and leads the Fraunhofer 'Science Communication' research group, which is based at the Fraunhofer Cluster of Excellence 'Integrated Energy Systems' CINES. She is also one of the principal investigators of the DFG Research Training Group 2720. She analyses public discussions on political issues such as digitalisation and climate change.

That also goes for my generation, which definitely does not consist of environmentally conscious saints. Many Fridays-for-Future activists themselves have a lifestyle that is harmful to the climate. It's the kind of lifestyle that we know from our parents and that we also feel we have a right to. But it's a lifestyle about which, to this very day, others have only ever been able to dream. People in countries of the global South for example, who will at the same time be those who suffer most under the consequences of the climate crisis. Indeed, they are already doing so. So how do things look down there with regard to the generation conflict?

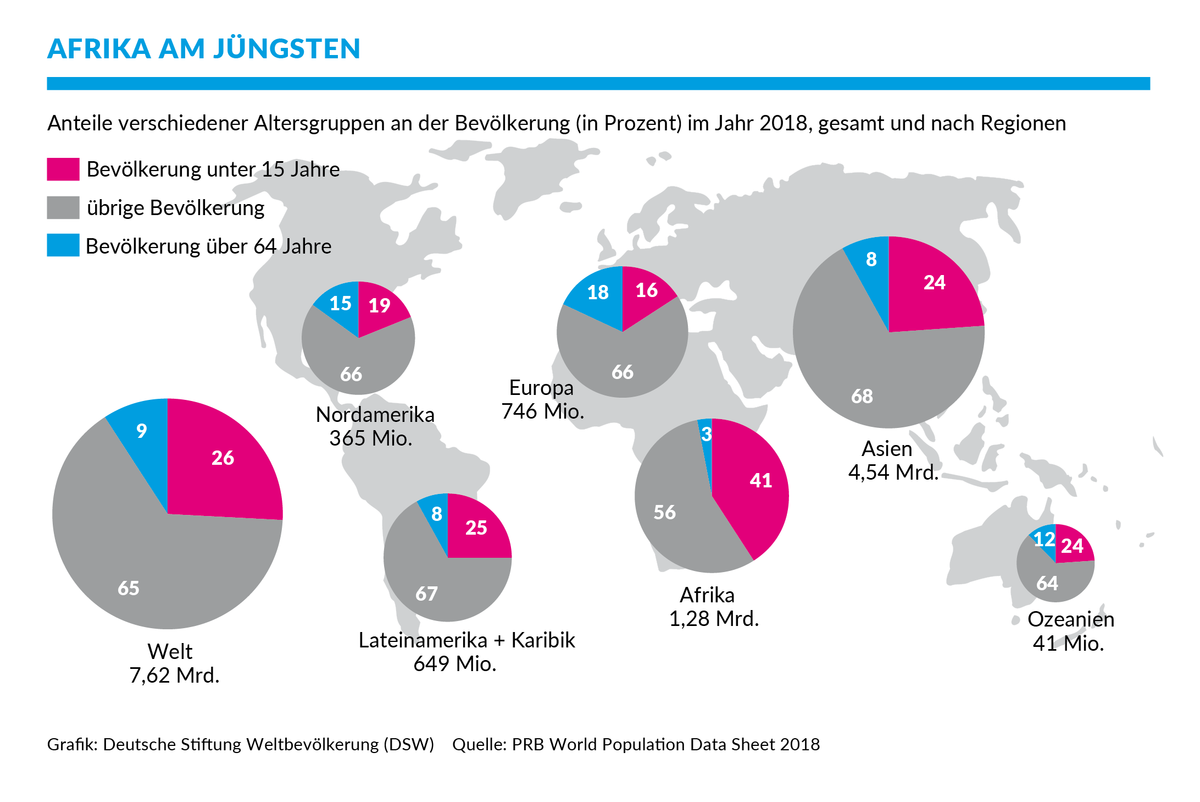

In 2018 there were 7,620,000,000 people living on the Earth, 26 per cent of whom were younger than 15. By contrast, only nine per cent were over 64. But a look at the demography in the countries of the global North, whose inhabitants make the biggest contribution to climate change, reveals a different picture of this age structure. In Europe, on account of the demographic transition, those over 64 are represented much more strongly at 18 per cent, whilst those under 15 only make up 16 per cent of the population. So in terms of the population as a whole, viewed globally, there are a lot more young people in other parts of the world than in Europe.

The conflict in global terms

Via Zoom, I meet up with the development economist Professor Michael Grimm, who has visited more than ten African countries for his field research, and several Asian ones as well. In terms of its population, Africa is the youngest of the seven continents by far: 19 of the 20 countries worldwide with the lowest average age in the population are on the African continent. "Why should a 60-year-old Ethiopian feel responsible for the greenhouse effect?" says Professor Grimm with a laugh.Statistically, many of the older people in countries of the global South are part of the generation which has made the biggest contribution to climate change, but the damage has mainly been caused by people in the global North. Moreover, the relationships between the generations in African countries are different to the ones we have: "The elders are greatly respected, and they are looked after, both socially and financially. As a matter of basic principle, there is tremendous solidarity between the generations. That has to do with the circumstance that the young help the older generation pay their way because the latter have no provision for old age." Accusations like the ones western youths level at their parents and grandparents would be culturally unthinkable in many countries of the global South.

Professor Michael Grimm

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

What are the measures that enable developing countries to participate in global market processes?

Professor Michael Grimm has held the Chair of Development Economics of the University of Passau since 2012. He is also one of the Principal Investigators of the DFG Research Training Group 2720 "Digital Platform Ecosystems (DPE)". Prior to this, he held the posts of Professor of Applied Development Economics at Erasmus University Rotterdam, Visiting Professor at Paris School of Economics and Advisor for the World Bank in Washington, D.C. (United States).

That unspoken inter-generational contract or, to put it another way, informal insurance scheme between the generations could bring about some particularly challenging developments in the context of climate change. In one of his research papers, for example, Professor Grimm shows that the birth rate is high in regions with major weather fluctuations, because children are often seen as a kind of provision for risks. By helping out in the household, they take the burden off their parents, who then have more time to work, or they top up the household income by doing simple jobs in the informal economy. In this way, children can help to compensate for economic setbacks such as crop failures. This effect will be exacerbated when extremes of weather become more frequent as a result of climate change. In concrete terms, that means that climate change may under certain circumstances lead to a situation in which even more people are born in the poorest regions of the world, who will then, in the long term, be the ones who suffer under its consequences – a vicious circle.

Out and about in the name of ecology: Student Janina Körber on the Oberer Stadtplatz in her home town of Schärding. The 23-year-old commutes to the university daily by train. Credits: Leo Heidemann

More power to the children?

However, if the climate crisis is going to have such grave consequences for future generations, they ought to be involved in the decisions that are being made today. One option for more involvement of young people in democratic societies would be to lower the voting age. Youth associations such as the German Federal Youth Council (DBJR) have been calling for that for years, so that young people can have a bigger say in what goes on. However, there is no consensus about what the voting age should be lowered to. And there is plenty of opposition to these initiatives – possibly also because the results of under-18 elections traditionally differ greatly from those of the official elections. The turnout at under-18 elections indicates that young people have a considerable interest in political co-determination. At the under-18 federal election in Germany in 2017, for example, 220,000 young people turned out to vote.

Should inter-generational equity be anchored in German Basic Law?

In fact, however, it is already the case that politicians must consider the consequences of the decisions they make for future generations. One thing many people do not know is that sustainability is a codified national objective in Germany, in other words a binding standard for government action. Article 20a of German Basic Law (GG) states that 'mindful also of its responsibility towards future generations, the state shall protect the natural foundations of life and animals.' That sounds pretty good, doesn't it? I ask Professor Jörg Fedtke, holder of the Chair of Common Law, why the effect of this national objective has so far been modest: "No-one actually wants to go as far as to implement Article 20a systematically, because people don't want to be restricted to that extent. That wouldn't be capable of gaining a majority in a democracy at the present time." If we were to do justice to that national objective, our life really would have to change radically. That would be an incision of the kind that until now most politicians have not had the courage to make, since they always have the forthcoming elections at the back of their mind.

However, Professor Fedtke does see one practical possibility for a solution in a compulsory environmental impact assessment of each draft law, such as has existed in France since 2005: 'In Germany so far, each draft has been reviewed by a commission with regard to the costs it will incur and the amount of bureaucracy it will engender. What we need is a third review, i.e. one of sustainability.'

Back at the station, where there are also many on-the-spot checks, though they are concerned more at present with whether or not the people are wearing their mask and not so much with whether or not they leave their engine running while they're waiting. I've learned that collective accusations are not just pointless, but that in cases of doubt they actually cause factions with opposing views to dig in more deeply. And I can also see that in the way the elderly gentleman reacts. He gives me a withering look. But at least he's cut his engine.

About the author

Janina Körber is studying media and communication at the University of Passau. Since 2017, the 23-year-old environmental activist has been chairwoman of the Bavarian section of the Young Friends of Nature (NFJB). She is committed to the social-ecological transformation of society and holds workshops on right-wing extremism in Nature conservation and environmental protection. She also works as a student assistant in the department of research communication at the University of Passau. The article "Devant nous le déluge" was written during the study seminar "Communicating sustainability – making sure they get the message" under Dr. Stephanie Lehmann.