When the Chair of Digital Humanities was established in 2013, it was one of the very few in Europe's research landscape. This discipline at the interface between the humanities and information technology has now grown and gained in reputation – more than just a whiff of the pioneering spirit lingers on, though, and continues to breathe through Room 105, the Laboratory for Cultural Heritage Digitisation at Hans-Kapfinger-Straße. This is where the reflectors and levers, lights, cameras and dials of the appliances lined up in a neat row create an atmosphere somewhere between that of an autopsy room, photo studio and computer centre.

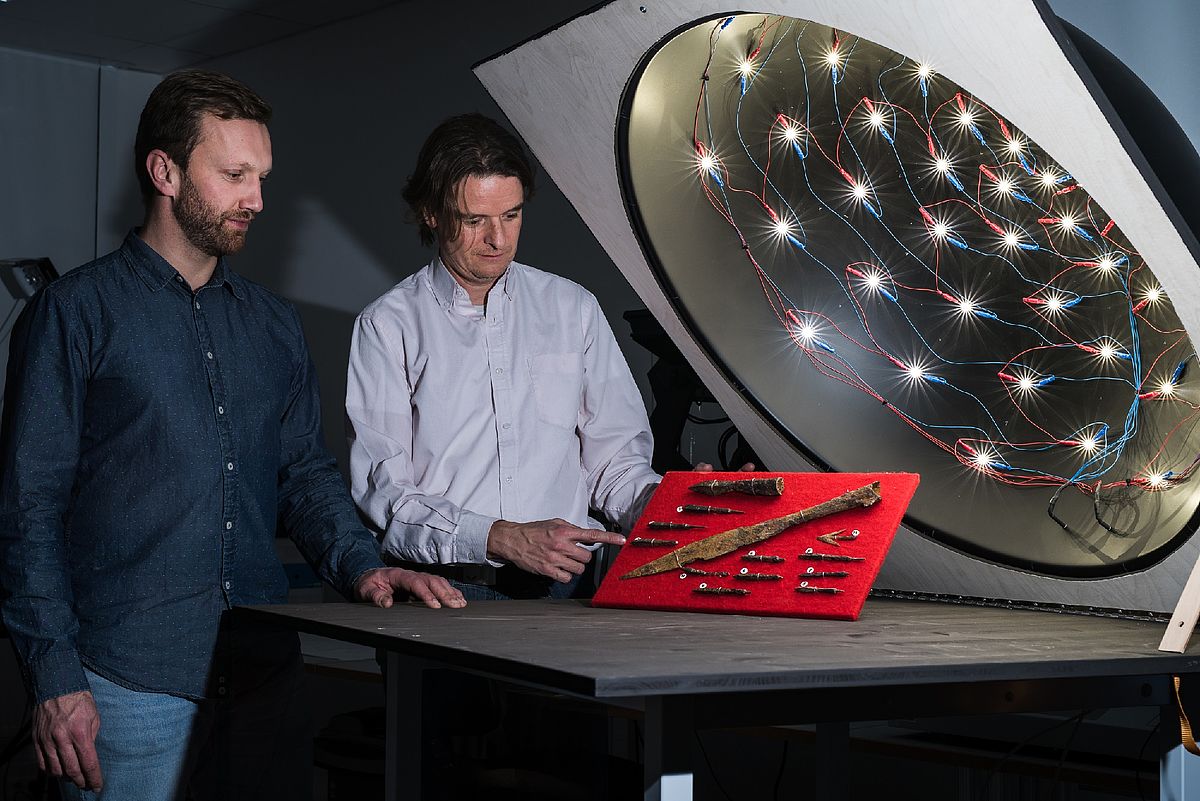

Professor Malte Rehbein and his colleague Sebastian Gassner stand bent over a collection of impressive arrowheads, spearheads and crossbow quarrels carefully arranged in the middle of the table. Found in Julbach in Lower Bavaria, they date back to the late Middle Ages. The dome of the Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) machine is about to be lowered onto the objects to take pictures of them from 64 different angles of illumination. At a later stage, the computer will combine these into a multidimensional digital image which is supposed to stand the test of time and outlive the originals.

The various processes used to digitise two- and three-dimensional cultural heritage objects are systematically tested and improved in the laboratory – because the artefact itself and the information that is being sought ultimately determine which procedure is appropriate. The scalability of the system makes lots of things technically possible: whatever works for the arrowhead from Julbach can be done with an entire castle. ‘Cultural heritage digitisation is a key pillar of our work,’ Rehbein says as he draws himself up. ‘Whether we analyse data, explore historical networks or deliberate the effects of digitisation on science and society on a meta-level – it all begins here where we come into contact with the artefacts and written documents, with the sources of our culture.’

Research and Teaching Laboratory for the Humanities

Given this modus operandi, however, the Digital Humanities at Passau are, after all, rather a special case: no German university has ever before had this kind of research and teaching laboratory for the humanities. ‘It's really rather special,’ says Malte Rehbein, not without pride.

In their historical research, Rehbein and his team primarily use metadata describing the characteristics of the digitalised object: material, colour, size, function, age, origin, maker – all these pieces of information can be linked together, put into relation with one another and integrated into larger knowledge networks. In another research focus, the team studies the networks of historical persons, drawing the necessary information from the written sources that have been digitised in the laboratory: ‘We want to find out who was related to whom in what way or who was in contact with whom; in other words, we want to explore the structural constellations that existed in the past. The methodical approach employed for this purpose is similar to the one used in social network analysis,’ explains Rehbein.

‘Interdisciplinary networking is the foundation of what we do’

Research on networks itself relies on networks. ‘Digital humanities would not be possible without specialist disciplines such as the historical sciences. You could say that interdisciplinary networking is the foundation of what we do,’ emphasises Rehbein. This becomes evident in the ViSIT project, for example, which receives two million euros in funding from the EU's INTERREG V-A programme ‘Austria – Bavaria 2014–2020’. In addition to Rehbein's, five other chairs of the University of Passau are involved:

- Data Science (Professor Michael Granitzer)

- Distributed Information Systems (Professor Harald Kosch)

- Information Systems (Professor Franz Lehner)

- Digital Image Processing (Professor Tomas Sauer)

- Art History and Visual Culture Studies (Professor Jörg Trempler)

Together, the cultural researchers and computer experts are now developing a digital infrastructure that will make the shared history of castles situated across the border region between Passau and Kufstein tangible for visitors, no matter which castle they are currently at. Further research partners, several cultural memory institutions and a number of municipalities are likewise involved. In this case, too, the long-term objective is a network idea: ‘For this part of our shared history, we want to create an integrated digital system, a type of virtual museum that provides the participating institutions with new modes of presentation and hence also wins them new audiences.’

Against this backdrop, the laboratory in Passau again serves as an interface, facilitating a transfer that is seen as a major enrichment for the institutions dedicated to the preservation of culture, as Dr Bernhard Forster, cultural advisor for the City of Passau, underscores: ‘Digitisation is a massive topic for cultural work in the City of Passau, too, of course. That is why we look forward very much to working with the Digital Humanities Chair, be it in the ViSIT project of Passau’s Castle Museum or the digitisation of documents from the City Archives – like those of the estate of Eduard Hamm, for example. This is vital for the preservation of our collections over the long run and, at the same time, for making them much easier to access in virtual form for the public at large.’

This article is taken from the issue 02/2017 of the Campus magazine

![[Translate to English:] Prof. Dr. Malte Rehbein im Labor für Kulturgutdigitalisierung](https://www.digital.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/_processed_/a/e/csm__DSC1928_rehbein_0fd73b100d.jpg)